Blog

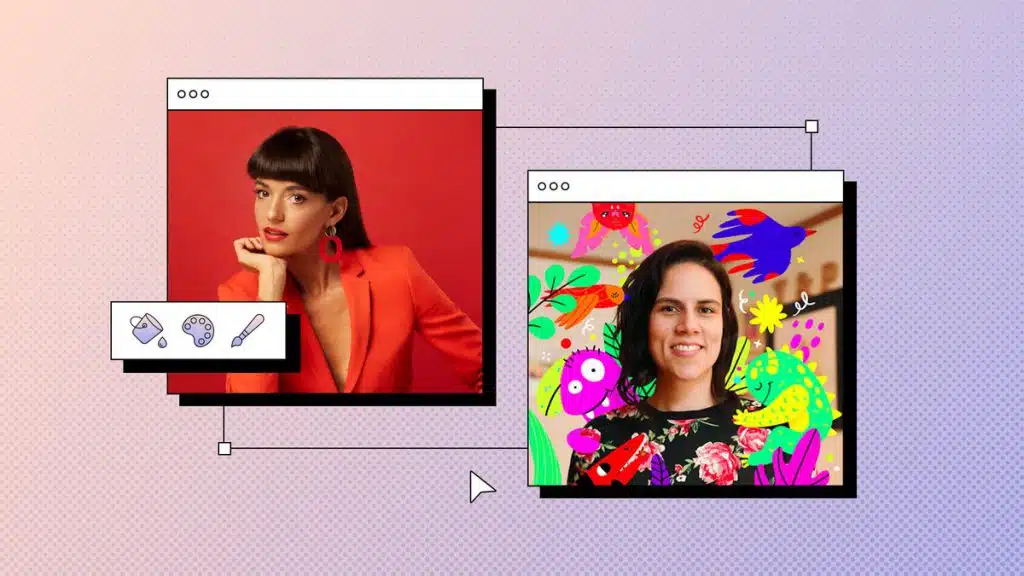

Learn How to Use Photoshop With These 10 Free Courses and Tutorials

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Printers and texts, but also newspapers and magazines in columns and rows as needed and for the current state of technology required and a variety of applications with the aim of improving practical tools. Sixty-three percent of books in the past, present and future require a lot of knowledge from the community and professionals to create more knowledge with software for computer designers, especially creative designers and leading culture in the Persian language. In this case, it can be hoped that all the difficulties in presenting solutions and difficult typing conditions will end and the time required, including typing the main achievements and answering the continuous questions of the existing world of design, will be basically used. Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit.